MONUMENT MATERIALS

Granite

Most Victorians preferred granite as the material of choice for a cemetery monument. It was particularly hard and durable. And it could be obtained in a wide variety of colors and crystalline textures to suit individual tastes.

Marble

Marble was an important second choice as a cemetery monument material after granite. Marble also comes in a wide range of quality, some are proving to be quite permanent, some not. Acid rain has caused severe damage to the poorer grades of marble. Many of the sculptures atop monuments are carved in marble.

White Bronze – Zinc

There are many monuments in Mt. Hope that appear to be made of a bluish grey stone. These monuments are actually made of moulded metal! The material was called White Bronze to make it more appealing to customers, but it is actually pure zinc. Left exposed to the elements the monuments rapidly form a tough and very durable skin of zinc carbonate that protects the underlying metal. The zinc carbonate is what gives the monuments their characteristic bluish grey color. The monuments were erected in cemeteries across the entire United States (including Hawaii) and Canada.

These monuments were ordered from a sales agent with a catalogue, and were very inexpensive. The price range for these monuments was from about $6 for a single cast tablet, to as much as $5,000. The White Bronze markers copied the same shapes and styles as marble and granite monuments, but the stone monument dealers seldom sold the metal monuments. The back of the catalogue featured an ad asking people to become sales agents with ”No capital investment needed.”

The catalogues listed the various shapes, symbols, sculptures, and panels that could be used. The customer would decide on the overall design he wanted, and then pick out the various symbols, and other decorative elements required. Price was based on the over all monument, not the number of images. Customers often ordered several images for each side. The individual pieces were then moulded in zinc, and then simply bolted together with screws with decorated heads. Any text required was easily moulded in the same fashion. When other family members died at a later date, old decorative panels could be easily removed and replaced with new castings with the updated information.

M.A. Richardson and C.J. Willard perfected the method of casting in 1873, but they did not have the capital that was required for full scale manufacturing, so they sold out to W.W. Evans. Evans also failed to get anything started, and sold the process to the Wilson, Parsons & Company of Bridgeport Connecticut in 1874.

The Monumental Bronze Company made the monuments from until 1914 when the he government took over the plant for the manufacturing of munitions during World War I. In the post war years the demand for the monuments had faded, so the company turned to making castings for automobiles and radios until it closed in 1939.

Monumental Bronze opened its first subsidiary in Detroit in 1881. Detroit Bronze operated until 1885. Two more subsidiaries opened in 1886. American Bronze operated in Chicago for twenty-three years, until it closed in 1909. Western White Bronze Company in Des Moines operated for twenty-two years, and closed in 1908. These subsidiaries did not do castings; they were only involved in the final assembly of the pieces. All the original casting took place in Bridgeport Connecticut.

It possible to find dates of death from both before and after Monumental Bronze made the monuments. The company would produce panels for family members who had died before the monument was ordered, and they continued to make individual panels after they stopped production of complete monuments in 1914.

Wax models were created by an artist, who worked at the plant. His models were then used to create plaster moulds for creating the individual pieces. The company used a patented process for fusing the larger pieces together. Zinc was heated to temperatures way above its melting point, and then poured into the joints between individual pieces. This caused the adjoining surfaces to melt together, welding them into a single unit, a much stronger process than soldering.

The company used a patented process for fusing the larger pieces together. Zinc was heated to temperatures way above its melting point, and then poured into the joints between individual pieces. This caused the adjoining surfaces to melt together, welding them into a single unit, a much stronger process than soldering.

The zinc carbonate that gives the monuments their characteristic bluish grey color also creates a hard protective skin so that the castings are still extremely sharp and clear. However, zinc has two unfortunate characteristics. It is quite brittle and may break if hit by a falling branch, and over many years it’s unsupported weight will creep and sag, causing some of the larger monuments to bow or crack. Another problem, but one that affects all cemetery monuments, is poor foundations. Crumbling bases and shifting soil has caused many monuments to lean.

The general rarity of these monuments is due to the fact that they were only produced for 40 years. This short production was caused by the fact that the metal monuments were never accepted by the public. Some cemeteries passed regulations that prohibited the use of metal markers, but it was mostly because people did not fully accept the claims that these monuments were superior to stone. Interesting enough time has shown that these inexpensive zinc monuments have remained in excellent condition for over a century, with details as fresh and crisp as the day they were cast.

Sandstone

Another uncommon material for cemetery monuments is sandstone. The sandstone used in Mt. Hope Cemetery is the Medina Sandstone, named for the small town about halfway between Rochester and Niagara Falls. The red, or Grimsby Sandstone, is the variant of the Medina used. A very popular building material. It was used on many buildings in downtown Rochester, and for curbing throughout the city. Although harder than some of the local limestones, it is easier to work with. Rubbing your fingers on its surface gives a gritty feeling, as the stone breaks back down into sand.

Very susceptible to weathering, it proved to be a poor choice for monuments. The erosion can easily be seen on Lewis Henry Morgan’s tomb.

Slate

There are very few slate monuments in Mount Hope. Slate monuments tend to flake and split destroying their carved inscriptions. The Victorians noted this and changed to the more durable granite.

Fletcher Steele, a Pittsford resident, was a world famous landscape architect. He designed the four classic shouldered tablet stones that mark the graves of the members of his family. He chose a black slate of exceptionally high quality and created four monuments that are typical of the slate headstones found in his native New England graveyards.

MONUMENT TYPES

Tablets & Headstones

This type is the most popular and frequently encountered grave memorial found in old cemeteries. A variety of materials have been used for this type of memorial, ranging from wood to stone. While there are many shapes and sizes of tablets and headstones, most exhibit a few common features. First, most are not enormous monuments. They tend to be 80 to 100 centimetres in height and vary in thickness from 8 to 20 centimetres. The headstone may be placed by itself in the ground or may be set on a base or on top of another grave structure such as a ground ledger. The term “headstone” derives from the position of the stone above the interred corpse’s head. Once it was common to use a headstone and a smaller stone a short distance away called the footstone. Footstones were usually made of the same material as the headstone but were much smaller. The footstone was usually inscribed with the initials of the deceased.

Simple tablet

Tends to be rectangular and the same thickness throughout; no curves, angles or tapering features. Faces may be polished or plain. Simple lines of construction.

Domed tablet

Tends to have more angles and may be the same thickness throughout or thicker at the base. Tapers to a domed top having a convex shape or sloping angles.

Shouldered tablet

Tends to have far more intricate angles and cuts on the top portion of the headstone. There is much variation in this type of tablet.

Gothic tablet

Similar to the domed tablet, but the angles along the top of the headstone and the shoulders are steeper. Same styling as the Gothic arches popular in European churches.

Rustic tablet/headstone

Tends to be thicker and more robust than other designs. It is common to see these memorials with a pattern that looks almost like a stone wall. The main inscription face is usually polished and the polished section may be in the shape of a large arrow pointing upward (direct line to heaven). The hymn “Rock of Ages” is said to have inspired the popularity of rustic tablets in the 1920s and 1930s.

MARKERS

This type of grave memorial is also common in old cemeteries, and they can be found set into a base, on a ground ledger or just by themselves. Most markers tend to be thicker than headstones/tablets and lower to the ground. The one exception is the plaque, which is quite thin. Where tablets/headstones are made of almost any material, markers tend to be made from stone, cement or bronze. There are great variations in the sizes of markers, from tiny ones on children’s graves to huge monumental ones on prominent family grave sites. Because markers are lower to the ground, much bulkier and constructed of more

durable material, little damage has occurred to them over the years.

The following are some of the most common types of markers:

Ledger

Ground Ledgers are rectangular in shape, taking the dimensions of the grave itself. They are usually made of granite, sandstone or marble. They are bulkier and constructed low to the ground. All of these factors contribute to the long life expediency of these markers.

Simple block

Rectangular block that tends to be quite thick. Usually made of marble or granite.

MONUMENT MATERIALS

Granite

Most Victorians preferred granite as the material of choice for a cemetery monument. It was particularly hard and durable. And it could be obtained in a wide variety of colors and crystalline textures to suit individual tastes.

Marble

Marble was an important second choice as a cemetery monument material after granite. Marble also comes in a wide range of quality, some are proving to be quite permanent, some not. Acid rain has caused severe damage to the poorer grades of marble. Many of the sculptures atop monuments are carved in marble.

White Bronze – Zinc

There are many monuments in Mt. Hope that appear to be made of a bluish grey stone. These monuments are actually made of moulded metal! The material was called White Bronze to make it more appealing to customers, but it is actually pure zinc. Left exposed to the elements the monuments rapidly form a tough and very durable skin of zinc carbonate that protects the underlying metal. The zinc carbonate is what gives the monuments their characteristic bluish grey color. The monuments were erected in cemeteries across the entire United States (including Hawaii) and Canada.

These monuments were ordered from a sales agent with a catalogue, and were very inexpensive. The price range for these monuments was from about $6 for a single cast tablet, to as much as $5,000. The White Bronze markers copied the same shapes and styles as marble and granite monuments, but the stone monument dealers seldom sold the metal monuments. The back of the catalogue featured an ad asking people to become sales agents with ”No capital investment needed.”

The catalogues listed the various shapes, symbols, sculptures, and panels that could be used. The customer would decide on the overall design he wanted, and then pick out the various symbols, and other decorative elements required. Price was based on the over all monument, not the number of images. Customers often ordered several images for each side. The individual pieces were then moulded in zinc, and then simply bolted together with screws with decorated heads. Any text required was easily moulded in the same fashion. When other family members died at a later date, old decorative panels could be easily removed and replaced with new castings with the updated information.

M.A. Richardson and C.J. Willard perfected the method of casting in 1873, but they did not have the capital that was required for full scale manufacturing, so they sold out to W.W. Evans. Evans also failed to get anything started, and sold the process to the Wilson, Parsons & Company of Bridgeport Connecticut in 1874.

The Monumental Bronze Company made the monuments from until 1914 when the he government took over the plant for the manufacturing of munitions during World War I. In the post war years the demand for the monuments had faded, so the company turned to making castings for automobiles and radios until it closed in 1939.

Monumental Bronze opened its first subsidiary in Detroit in 1881. Detroit Bronze operated until 1885. Two more subsidiaries opened in 1886. American Bronze operated in Chicago for twenty-three years, until it closed in 1909. Western White Bronze Company in Des Moines operated for twenty-two years, and closed in 1908. These subsidiaries did not do castings; they were only involved in the final assembly of the pieces. All the original casting took place in Bridgeport Connecticut.

It possible to find dates of death from both before and after Monumental Bronze made the monuments. The company would produce panels for family members who had died before the monument was ordered, and they continued to make individual panels after they stopped production of complete monuments in 1914.

Wax models were created by an artist, who worked at the plant. His models were then used to create plaster moulds for creating the individual pieces. The company used a patented process for fusing the larger pieces together. Zinc was heated to temperatures way above its melting point, and then poured into the joints between individual pieces. This caused the adjoining surfaces to melt together, welding them into a single unit, a much stronger process than soldering.

The company used a patented process for fusing the larger pieces together. Zinc was heated to temperatures way above its melting point, and then poured into the joints between individual pieces. This caused the adjoining surfaces to melt together, welding them into a single unit, a much stronger process than soldering.

The zinc carbonate that gives the monuments their characteristic bluish grey color also creates a hard protective skin so that the castings are still extremely sharp and clear. However, zinc has two unfortunate characteristics. It is quite brittle and may break if hit by a falling branch, and over many years it’s unsupported weight will creep and sag, causing some of the larger monuments to bow or crack. Another problem, but one that affects all cemetery monuments, is poor foundations. Crumbling bases and shifting soil has caused many monuments to lean.

The general rarity of these monuments is due to the fact that they were only produced for 40 years. This short production was caused by the fact that the metal monuments were never accepted by the public. Some cemeteries passed regulations that prohibited the use of metal markers, but it was mostly because people did not fully accept the claims that these monuments were superior to stone. Interesting enough time has shown that these inexpensive zinc monuments have remained in excellent condition for over a century, with details as fresh and crisp as the day they were cast.

Sandstone

Another uncommon material for cemetery monuments is sandstone. The sandstone used in Mt. Hope Cemetery is the Medina Sandstone, named for the small town about halfway between Rochester and Niagara Falls. The red, or Grimsby Sandstone, is the variant of the Medina used. A very popular building material. It was used on many buildings in downtown Rochester, and for curbing throughout the city. Although harder than some of the local limestone, it is easier to work with. Rubbing your fingers on its surface gives a gritty feeling, as the stone breaks back down into sand.

Very susceptible to weathering, it proved to be a poor choice for monuments. The erosion can easily be seen on Lewis Henry Morgan’s tomb.

Slate

There are very few slate monuments in Mount Hope. Slate monuments tend to flake and split destroying their carved inscriptions. The Victorians noted this and changed to the more durable granite.

Fletcher Steele, was a world famous landscape architect. He designed the four classic shouldered tablet stones that mark the graves of the members of his family. He chose a black slate of exceptionally high quality and created four monuments that are typical of the slate headstones found in his native New England graveyards.

MONUMENT TYPES

Tablets & Headstones

This type is the most popular and frequently encountered grave memorial found in old cemeteries. A variety of materials have been used for this type of memorial, ranging from wood to stone. While there are many shapes and sizes of tablets and headstones, most exhibit a few common features. First, most are not enormous monuments. They tend to be 80 to 100 centimetres in height and vary in thickness from 8 to 20 centimetres. The headstone may be placed by itself in the ground or may be set on a base or on top of another grave structure such as a ground ledger. The term “headstone” derives from the position of the stone above the interred corpse’s head. Once it was common to use a headstone and a smaller stone a short distance away called the footstone. Footstones were usually made of the same material as the headstone but were much smaller. The footstone was usually inscribed with the initials of the deceased.

Simple tablet

Tends to be rectangular and the same thickness throughout; no curves, angles or tapering features. Faces may be polished or plain. Simple lines of construction.

Domed tablet

Tends to have more angles and may be the same thickness throughout or thicker at the base. Tapers to a domed top having a convex shape or sloping angles.

Shouldered tablet

Tends to have far more intricate angles and cuts on the top portion of the headstone. There is much variation in this type of tablet.

Gothic tablet

Similar to the domed tablet, but the angles along the top of the headstone and the shoulders are steeper. Same styling as the Gothic arches popular in European churches.

Rustic tablet/headstone

Tends to be thicker and more robust than other designs. It is common to see these memorials with a pattern that looks almost like a stone wall. The main inscription face is usually polished and the polished section may be in the shape of a large arrow pointing upward (direct line to heaven). The hymn “Rock of Ages” is said to have inspired the popularity of rustic tablets in the 1920s and 1930s.

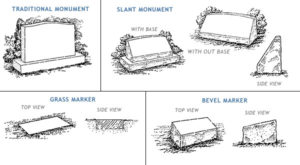

MARKERS

This type of grave memorial is also common in old cemeteries, and they can be found set into a base, on a ground ledger or just by themselves. Most markers tend to be thicker than headstones/tablets and lower to the ground. The one exception is the plaque, which is quite thin. Where tablets/headstones are made of almost any material, markers tend to be made from stone, cement or bronze. There are great variations in the sizes of markers, from tiny ones on children’s graves to huge monumental ones on prominent family grave sites.

Because markers are lower to the ground, much bulkier and constructed of more durable material, little damage has occurred to them over the years.

The following are some of the most common types of markers:

Ledger

Ground Ledgers are rectangular in shape, taking the dimensions of the grave itself. They are usually made of granite, sandstone or marble. They are bulkier and constructed low to the ground. All of these factors contribute to the long life expediency of these markers.

Simple block

Rectangular block that tends to be quite thick. Usually made of marble or granite.

Flat marker

Tends to be thinner than other markers and lies flat along the ground. May be set into a base or just by itself. Usually these markers have only enough room for a very simple inscription such as name, years of birth and death and a three- or four-word epitaph.

Plaque

Tends to be very thin and made of either bronze or brass. Can also be found on a slanting, raised foundation. Bronze is cast and shows very little deterioration over time. Lettering is usually in relief. Brass develops a patina with its reaction to the environment and leaves a green-coloured residue when in contact with water. Lettering is usually incised

Slant-faced marker

Comes in a variety of sizes and styles. Main characteristic is the slant of the inscription face, usually at a 40 to 45 degree angle, allowing the inscription to face a certain direction (usually east). This slant in the stone’s face allows for a greater surface area for inscriptions. Most often these markers are made of granite, marble or cement.

Scroll-faced marker

Tends to lie flat and is fashioned in the shape of a scroll, seen easily from the sides of the marker. The inscription is always placed on the scroll. The symbolic reference is to “divine law.” Most scroll-faced markers are made of granite but there are some examples in marble.

Open-book marker

Tends to lie flat and take on the dimensions of an open book (religious symbolism referring to the Bible or the word of God). This type of marker was very popular in the 1920s and 1930s. Almost all open-book markers are made of granite or marble. Very common on husband and wife burials with the husband’s inscription on the left, as in the marriage ceremony.

Vertical-face marker with slant-top

A flat vertical face with inscription on one side and the top of the marker has a sloping cut usually at a 45-degree angle. Generally no inscription is placed on the top. Although these stones are not common in larger city cemeteries, they do exist in moderate numbers in small older cemeteries in rural areas. This type of marker is usually made of white marble or granite.

Tree-Stump Tombstones

Tree-stump tombstones depict a lifelike tree and are traditionally carved out of limestone or marble. This tombstone first appeared in the 1870’s and was popular for approximately sixty years. Seen in Europe and the United States, these carvings qualify as folk art. The tree-stump design shows a living tree that has been cut down, suggesting that the individual was also cut down in the prime of life. Branches are also seen to be cut-off close to the stump, symbolising other family members who have died before their time. In some instances the initials of these family members appear to be carved into these cut-off limbs.

Inscriptions are cut into the “wood” where the bark has been cut away, or more often, a scroll appears nailed to the stump or suspended from a rope hanger. Various flowers and ivy are often carved as offerings at the base, or growing around the stump. An assortment of items are often seen on top of the stump, ranging from a cross, bible, anchor, flowers, or even the name and dates for the individual buried.

Obelisks, pedestals, & columns

The obelisk is, to quote McDowell and Meyer in The Revival Styles in American Memorial Art, one of the “most pervasive of all the revival forms” of cemetery art. There is hardly a cemetery founded in the 1840s and 50s without some form of Egyptian influence in the public buildings, gates, and tomb art. Napoleon’s 1798-99 Egyptian campaigns, the discoveries at the tombs of the Pharaohs, and our new Republic’s need to borrow the best of the ancient cultures (Greek revival, classic revival, the prominence of classical studies and dress, etc.) led to a resurgence of interest in the ancient Egyptian culture. Obelisks were considered to be tasteful, with pure uplifting lines, associated with ancient greatness, patriotic, able to be used in relatively small spaces, and, perhaps most importantly, obelisks were less costly than large and elaborate sculpted monuments.

Many of the largest and most spectacular monuments fall into this category. All obelisks and columns borrow heavily from Egyptian, Greek and Roman architectural styles. The original obelisk was square in section, tapering up to a pyramidal capital. During the 1800s, stonemasons used a variety of obelisk types, some with straight shafts and different tops from blunt (truncated Roman influence) to cross-vaulted on the top. Obelisks and columns have three distinct sections: the base (bottom support), the shaft (center column piece) and the capital (the top structure).

The one great advantage of obelisks, pilaster columns and pedestals is the available space for inscriptions. Where headstones and markers only have one inscription face, obelisks, columns and pedestals provide at least four inscription faces. These types of monuments are usually found on family burials or those of people of high social status. Because obelisks, columns and pedestals are higher, they also tend to stand out more in the cemetery and are easily located.

The following are some subtypes in this type:

Standard obelisk

Shaped like a finger or ray from the sun. Egyptian in origin to represent “Ra” the giver of all life. Usually made of granite, sandstone or marble. One variation is the white bronze obelisk made of cast zinc that appeared in the late 1800s, but had disappeared by the 1920s.

Truncated or blunt obelisk

Similar shape to the standard obelisk but with a rounded capital (top). Roman in origin, it appears to be a modification of the Egyptian obelisk. Usually made of sandstone, marble or granite.

Vaulted obelisks

Shaft is similar to the other obelisk styles but the capital (top) is distinctive. The most common variation is the cross-vaulted obelisk. The cross-vaulted obelisk’s capital peaks cross over, which gives a “+” or cross-vaulted pattern. On some of these vaulted obelisk styles, the capital is designed to look like the vaulted ceilings in churches.

Columns

Columns come in a variety of shapes and sizes similar to obelisks.

Gateway/bi-columnar monument

Usually appears as two columns supporting an arch. The columns can be Egyptian, Greek or Roman in styling. The columns and arch represent a gateway or entrance or what is referred to as “The portal to eternity.” Gateway columns are commonly found where the husband and wife are buried side by side. This monument type is also very common on Masonic graves. Usually gateway columns are free-standing, but can be found on top of ground ledgers. They also appear in a great variety of sizes and usually are made of either granite or marble.

Broken column

Usually in the classical Greek style or with a tapering shaft. Originated in England about 1815. Denotes the burial spot of a child or young person whose life was cut short.

Classical Greek column

Tends to have a straight shaft with flutes; shaft can taper slightly or be straight. Column may have an urn at the top. Usually made of marble or grey granite.

Standard column

Tends to have a rounded shaft that does not taper and has no flutes, but a smooth surface running up to the capital, usually with an urn on top. This type of column is usually made of marble, sandstone or granite.

Pilaster columns

Pilaster columns are a type of column, but are a combination of the obelisk and the column monument. The pilaster column has a square or rectangular shaft and is either flat topped or topped with an urn. The term “pilaster” can also be used to describe a support column protruding from a wall. The terminology is confusing because “pilasters” have been used both in descriptions of single free-standing columns and of eclectic monuments.

Romans appear to have first used this type of column, which was elaborately decorated with acanthus and garlands. The most famous historical pilaster is the “Pilaster from the Severna Basilica” in Italy, which is a rectangular column dating from the 3rd century A.D. and is elaborately carved out of marble. Because of the confusion, it is better to refer to pilasters as either “pilaster columns” (free-standing) or “pilasters” (eclectic memorials). Cemetery pilaster columns tend to be smaller than most other column memorials.

Sometimes pilaster columns are referred to as pedestals. Pedestal monuments are generally much thicker in the shaft and larger.

Stele

Greek, small column or pillar terminating in a cresting ornament and used as a monument.

Pedestal monument

Tends to be large, have four faces for inscriptions and flat vertical sides (tapering or straight) topped either with a flat capital or pediment (triangular roof-like structure). There may also be an urn above the pediment or the capital. The styling is adapted from architectural styles found in ancient Pompeii and usually is enriched with inscriptions, motifs and ornamental styling on four faces. Most often, these monuments are large and made of either granite or marble.

Eclectic monument

Tends to be large and incorporate two or three styles in one structure. This type of monument is commonly a large flat screen (for inscriptions) topped by either support pilasters or round or standard columns supporting a pediment capital. These monuments are generally massive and made of granite.

Crosses

The cross can take many forms and the symbolic meanings and history of each type is very complex and elaborate. Many types of crosses are used as cemetery monuments, but the four most often encountered as grave memorials are:

Latin cross

The Latin cross is common in Roman Catholic cemeteries or Catholic sections of cemeteries. Standard flat cross made of wood, granite, marble or granite. Very susceptible to damage because the cross bar or shoulders can be easily broken.

Calvary cross

This is a Latin cross mounted on a three-tiered base. The three-block base stands for the Trinity or faith, hope and charity (Protestant) or faith, hope and love (Roman Catholic). A Calvary cross can be made of any material, ranging from wood to stone.

Celtic cross

The Celtic cross dates back to the Celtic cultures of England, as early as the 5th century. Very elaborate decoration, highly ornate in styling. The center of the cross has a circular design that represents eternity. Almost always in granite or marble.

Rustic cross

This cross was a popular grave memorial in the 1920s and 1930s. The rustic appearance takes a form almost resembling wood. Almost always made of granite or marble, it may have a rough granite base.

DECORATIONS ON MONUMENTAL INSCRIPTIONS

These are some motifs found on gravestones with some of the commonly held

interpretations of their symbolism.

• Angel, Flying- Rebirth; Resurrection

• Angel, Trumpeting- Resurrection

• Angel, Weeping – Grief & Mourning

• Arch – Victory in Death

• Arrow – Mortality

• Bird – Eternal Life

• Bird, Flying – Resurrection

• Book – Representation of a holy book; i.e. the Bible

• Breasts (Gourds, Pomegranates) – Nourishment of the soul; the Church

• Columns and Doors – Heavenly entrance

• Crown – Glory of life after death

• Cup or Chalice – The Sacraments

• Dove – Purity; Devotion

• Dove, Flying – Resurrection

• Drapes – Mourning; Mortality

• Flame or Light – Life; Resurrection

• Flower – Fragility of Life

• Flower, Severed Stem – Shortened Life

• Garland or Wreath – Victory in Death

• Grim Reaper – Death personified

• Hand, Pointing Up – Pathway to Heaven; Heavenly Reward

• Hands, Clasped – The Goodbyes said at Death

• Heart – Love; Love of God; Abode of the Soul; Mortality

• Hourglass – Passing of Time

• Lamb – Innocence

• Lion – Courage; The Lion of Judah

• Pall – Mortality

• Pick – Death; Mortality

• Rod or Staff – Comfort for the bereaved

• Rooster – Awakening; Resurrection

• Scythe – Death; The Divine Harvest

• Seashell – Resurrection; Life Everlasting; Life’s Pilgrimage

• Skull – Mortality

• Skull/Crossed Bones – Death

• Skeleton – Life’s brevity

• Snake (Tail in Mouth) – Everlasting life in Heaven

• Spade – Mortality; Death

• Sun Rising – Renewed Life

• Sun Shining – Life Everlasting

• Sun Setting – Death

• Thistle – Scottish Descent

• Tree – Life

• Tree Sprouting – Life Everlasting

• Severed Branch – Mortality

• Tree Stump – Life Interrupted

• Tree Trunk – Brevity of Life

• Tree Trunk Leaning – Short Interrupted Life

• Urn – Immortality (Ancient Egyptian belief that life would be restored in the future through the vital organs placed in the urn.)

• Weeping Willow Tree – Mourning; Grief; Nature’s Lament

• Winged Face – Effigy of the Deceased Soul; the Soul in Flight

• Winged Skull – Flight of the Soul from Mortal man

• Wreath – Victory

• Wreath on Skull – Victory of Death over Life

• Wheat Strands or Sheaves – The Divine Harvest

GENERAL DEFINITIONS FOR BURIAL PLACES

Cairn:

A mound of stones erected as a memorial or marker.

Catacomb:

An underground cemetery consisting of chambers or tunnels with recesses for graves. The most celebrated catacombs are those near Rome, Italy. Cairo and Paris also have catacombs.

Cenotaph:

A monument erected honoring a dead person whose remains lie elsewhere.

Crypt:

An underground vault or chamber, especially one beneath a church that is used as a burial place.

Grave:

1. An excavation for the interment of a corpse.

2. A place of burial.

Mausoleum:

A large stately tomb or a building housing such a tomb or several tombs.

Tomb:

1. A grave or other place of burial.

2. A vault or chamber for burial of the dead.

3. A monument commemorating the dead.

Sepulchre:

A burial vault.

Vault:

A burial chamber, especially when underground.

Monument Typology:

Any structure placed over a grave should be considered a monument, whether it be a large elaborate tomb or a small wooden marker. For simplicity sake, we are dividing monuments into three separate categories; tombs, crypts, &c.; grave-houses and grave-shelters; and the smaller markers such as headstones and footstones.

Tombs

Megalith Style Monuments:

A very large stone forming part of a prehistoric structure. Sometimes used to describe a grave monument. Four large stones (one at each corner of a grave) then might be called a megalithic monument or structure.

Rectangular (Box) Shaped Burial Monuments

Box Tomb (Slab), Box Grave, Chest Tomb

Stone Tomb (Riprap with Slab Top)

Slot and Tab Tomb (Slab)

Table Tomb (With Ledger Stone Slab Top), Pedestal Tomb

Triangular Monuments (cairns)

Coffin Shaped Tomb

Shaped Stacked Stone Tomb

Shaped Stacked Stone Tomb

Stacked Stone Tomb

Step-Stone Tomb (Large Stone)

Step-Stone Tomb with Headstone and Footstone

Step-Stone Tomb (Large Stone) with Coffin Shaped Top

Step-Stone Tomb (Small Stone) with Headstone

Tent Grave (Slab Tent with Headstone and Footstone)

Tent Grave (Slab Tent without Headstone and Footstone)

Ledger Stone

Ledger Stone (Slab with Headstone and Footstone)

Ledger Stone (Slab without Headstone and Footstone)

Coffin Shaped Ledger Stone

Ledger Stone (Slab without Inscription)

Grave-houses and Grave-shelters (grave-box, grave-house, grave house, grave shed, grave shelter, lattice hut, spirit house)

Grave house (Wood on a Stone Foundation)

Grave Shelter (Wood)

USUAL GRAVE HOUSE MATERIALS

Brick

Concrete, also called “Cement”

Field Stone (fieldstone)

Limestone

Marble

Native Stone

Sandstone

Soapstone

Wood

GRAVE MARKERS, HEAD STONE TYPES

COMMON AND NOT SO COMMON GRAVE MARKER MATERIALS

Brick

Bronze

Cast Iron

Ceramic

Concrete, also improperly called “Cement”

Field Stone (fieldstone)

Granite

Limestone

Marble

Native Stone

Sandstone

Soapstone

White Bronze (zinc)

Wood

COMMON MARKER SHAPES

Round top

Column

Cross

Monolith

Monument

Obelisk

Pillar

Pyramid

Star of David

Foot Stone (footstone)

Head Stone (headstone)

Ledger Stone

Plinth (a base for a column, tomb, or grave marker)

Stone

Table Stone

Tomb Stone (tombstone)

Epitaph

ADORNMENTS FOR TOMBS AND MARKERS

Christian

Crosses

Independent Order of Odd Fellows (I.O.O.F.)

Jewish

Masonic, (Free and Accepted Masons – F.& A.M.)

Memento Mori (Dark Memento)

A reminder of death or mortality, especially a death-head or an angel of death.

Hatchment

A diamond-shaped panel or escutcheon bearing the coat of arms of a deceased person. Occasionally seen carved on headstones.

Flat marker

Tends to be thinner than other markers and lies flat along the ground. May be set into a base or just by itself. Usually these markers have only enough room for a very simple inscription such as name, years of birth and death and a three- or four-word epitaph.

Plaque

Tends to be very thin and made of either bronze or brass. Can also be found on a slanting, raised foundation. Bronze is cast and shows very little deterioration over time. Lettering is usually in relief. Brass develops a patina with its reaction to the environment and leaves a green-coloured residue when in contact with water.

Lettering is usually incised

Slant-faced marker

Comes in a variety of sizes and styles. Main characteristic is the slant of the inscription face, usually at a 40 to 45 degree angle, allowing the inscription to face a certain direction (usually east). This slant in the stone’s face allows for a greater surface area for inscriptions. Most often these markers are made of granite, marble or cement.

Scroll-faced marker

Tends to lie flat and is fashioned in the shape of a scroll, seen easily from the sides of the marker. The inscription is always placed on the scroll. The symbolic reference is to “divine law.” Most scroll-faced markers are made of granite but there are some examples in marble.

Open-book marker

Tends to lie flat and take on the dimensions of an open book (religious symbolism referring to the Bible or the word of God). This type of marker was very popular in the 1920s and 1930s. Almost all open-book markers are made of granite or marble. Very common on husband and wife burials with the husband’s inscription on the left, as in the marriage ceremony.

Vertical-face marker with slant-top

A flat vertical face with inscription on one side and the top of the marker has a sloping cut usually at a 45-degree angle. Generally no inscription is placed on the top. Although these stones are not common in larger city cemeteries, they do exist in moderate numbers in small older cemeteries in rural areas. This type of marker is usually made of white marble or granite.

Tree-Stump Tombstones

Tree-stump tombstones depict a lifelike tree and are traditionally carved out of limestone or marble. This tombstone first appeared in the 1870’s and was popular for approximately sixty years. Seen in Europe and the United States, these carvings qualify as folk art. The tree-stump design shows a living tree that has been cut down, suggesting that the individual was also cut down in the prime of life. Branches are also seen to be cut-off close to the stump, symbolising other family members who have died before their time. In some instances the initials of these family members appear to be carved into these cut-off limbs.

Inscriptions are cut into the “wood” where the bark has been cut away, or more often, a scroll appears nailed to the stump or suspended from a rope hanger. Various flowers and ivy are often carved as offerings at the base, or growing around the stump. An assortment of items are often seen on top of the stump, ranging from a cross, bible, anchor, flowers, or even the name and dates for the individual buried.

Obelisks, pedestals, & columns

The obelisk is, to quote McDowell and Meyer in The Revival Styles in American Memorial Art, one of the “most pervasive of all the revival forms” of cemetery art. There is hardly a cemetery founded in the 1840s and 50s without some form of Egyptian influence in the public buildings, gates, and tomb art. Napoleon’s 1798-99 Egyptian campaigns, the discoveries at the tombs of the Pharaohs, and our new Republic’s need to borrow the best of the ancient cultures (Greek revival, classic revival, the prominence of classical studies and dress, etc.) led to a resurgence of interest in the ancient Egyptian culture. Obelisks were considered to be tasteful, with pure uplifting lines, associated with ancient greatness, patriotic, able to be used in relatively small spaces, and, perhaps most importantly, obelisks were less costly than large and elaborate sculpted monuments.

Many of the largest and most spectacular monuments fall into this category. All obelisks and columns borrow heavily from Egyptian, Greek and Roman architectural styles. The original obelisk was square in section, tapering up to a pyramidal capital. During the 1800s, stonemasons used a variety of obelisk types, some with straight shafts and different tops from blunt (truncated Roman influence) to cross-vaulted on the top. Obelisks and columns have three distinct sections: the base (bottom support), the shaft (center column piece) and the capital (the top structure).

The one great advantage of obelisks, pilaster columns and pedestals is the available space for inscriptions. Where headstones and markers only have one inscription face, obelisks, columns and pedestals provide at least four inscription faces. These types of monuments are usually found on family burials or those of people of high social status. Because obelisks, columns and pedestals are higher, they also tend to stand out more in the cemetery and are easily located.

The following are some subtypes in this type:

Standard obelisk

Shaped like a finger or ray from the sun. Egyptian in origin to represent “Ra” the giver of all life. Usually made of granite, sandstone or marble. One variation is the white bronze obelisk made of cast zinc that appeared in the late 1800s, but had disappeared by the 1920s.

Truncated or blunt obelisk

Similar shape to the standard obelisk but with a rounded capital (top). Roman in origin, it appears to be a modification of the Egyptian obelisk. Usually made of sandstone, marble or granite.

Vaulted obelisks

Shaft is similar to the other obelisk styles but the capital (top) is distinctive. The most common variation is the cross-vaulted obelisk. The cross-vaulted obelisk’s capital peaks cross over, which gives a “+” or cross-vaulted pattern. On some of these vaulted obelisk styles, the capital is designed to look like the vaulted ceilings in churches.

Columns

Columns come in a variety of shapes and sizes similar to obelisks.

Gateway/bi-columnar monument

Usually appears as two columns supporting an arch. The columns can be Egyptian, Greek or Roman in styling. The columns and arch represent a gateway or entrance or what is referred to as “The portal to eternity.” Gateway columns are commonly found where the husband and wife are buried side by side. This monument type is also very common on Masonic graves. Usually gateway columns are free-standing, but can be found on top of ground ledgers. They also appear in a great variety of sizes and usually are made of either granite or marble.

Broken column

Usually in the classical Greek style or with a tapering shaft. Originated in England about 1815. Denotes the burial spot of a child or young person whose life was cut short.

Classical Greek column

Tends to have a straight shaft with flutes; shaft can taper slightly or be straight. Column may have an urn at the top. Usually made of marble or grey granite.

Standard column

Tends to have a rounded shaft that does not taper and has no flutes, but a smooth surface running up to the capital, usually with an urn on top. This type of column is usually made of marble, sandstone or granite.

Pilaster columns

Pilaster columns are a type of column, but are a combination of the obelisk and the column monument. The pilaster column has a square or rectangular shaft and is either flat topped or topped with an urn. The term “pilaster” can also be used to describe a support column protruding from a wall. The terminology is confusing because “pilasters” have been used both in descriptions of single free-standing columns and of eclectic monuments.

Romans appear to have first used this type of column, which was elaborately decorated with acanthus and garlands. The most famous historical pilaster is the “Pilaster from the Severna Basilica” in Italy, which is a rectangular column dating from the 3rd century A.D. and is elaborately carved out of marble. Because of the confusion, it is better to refer to pilasters as either “pilaster columns” (free-standing) or “pilasters” (eclectic memorials). Cemetery pilaster columns tend to be smaller than most other column memorials. Sometimes pilaster columns are referred to as pedestals. Pedestal monuments are generally much thicker in the shaft and larger.

Stele

Greek, small column or pillar terminating in a cresting ornament and used as a monument.

Pedestal monument

Tends to be large, have four faces for inscriptions and flat vertical sides (tapering or straight) topped either with a flat capital or pediment (triangular roof-like structure). There may also be an urn above the pediment or the capital. The styling is adapted from architectural styles found in ancient Pompeii and usually is enriched with inscriptions, motifs and ornamental styling on four faces. Most often, these monuments are large and made of either granite or marble.

Eclectic monument

Tends to be large and incorporate two or three styles in one structure. This type of monument is commonly a large flat screen (for inscriptions) topped by either support pilasters or round or standard columns supporting a pediment capital. These monuments are generally massive and made of granite.

Crosses

The cross can take many forms and the symbolic meanings and history of each type is very complex and elaborate. Many types of crosses are used as cemetery monuments, but the four most often encountered as grave memorials are:

Latin cross

The Latin cross is common in Roman Catholic cemeteries or Catholic sections of cemeteries. Standard flat cross made of wood, granite, marble or granite. Very susceptible to damage because the cross bar or shoulders can be easily broken.

Calvary cross

This is a Latin cross mounted on a three-tiered base. The three-block base stands for the Trinity or faith, hope and charity (Protestant) or faith, hope and love (Roman Catholic). A Calvary cross can be made of any material, ranging from wood to stone.

Celtic cross

The Celtic cross dates back to the Celtic cultures of England, as early as the 5th century. Very elaborate decoration, highly ornate in styling. The center of the cross has a circular design that represents eternity. Almost always in granite or marble.

Rustic cross

This cross was a popular grave memorial in the 1920s and 1930s. The rustic appearance takes a form almost resembling wood. Almost always made of granite or marble, it may have a rough granite base.

DECORATIONS ON MONUMENTAL INSCRIPTIONS

These are some motifs found on gravestones with some of the commonly held

interpretations of their symbolism.

• Angel, Flying- Rebirth; Resurrection

• Angel, Trumpeting- Resurrection

• Angel, Weeping – Grief & Mourning

• Arch – Victory in Death

• Arrow – Mortality

• Bird – Eternal Life

• Bird, Flying – Resurrection

• Book – Representation of a holy book; i.e. the Bible

• Breasts (Gourds, Pomegranates) – Nourishment of the soul; the Church

• Columns and Doors – Heavenly entrance

• Crown – Glory of life after death

• Cup or Chalice – The Sacraments

• Dove – Purity; Devotion

• Dove, Flying – Resurrection

• Drapes – Mourning; Mortality

• Flame or Light – Life; Resurrection

• Flower – Fragility of Life

• Flower, Severed Stem – Shortened Life

• Garland or Wreath – Victory in Death

• Grim Reaper – Death personified

• Hand, Pointing Up – Pathway to Heaven; Heavenly Reward

• Hands, Clasped – The Goodbyes said at Death

• Heart – Love; Love of God; Abode of the Soul; Mortality

• Hourglass – Passing of Time

• Lamb – Innocence

• Lion – Courage; The Lion of Judah

• Pall – Mortality

• Pick – Death; Mortality

• Rod or Staff – Comfort for the bereaved

• Rooster – Awakening; Resurrection

• Scythe – Death; The Divine Harvest

• Seashell – Resurrection; Life Everlasting; Life’s Pilgrimage

• Skull – Mortality

• Skull/Crossed Bones – Death

• Skeleton – Life’s brevity

• Snake (Tail in Mouth) – Everlasting life in Heaven

• Spade – Mortality; Death

• Sun Rising – Renewed Life

• Sun Shining – Life Everlasting

• Sun Setting – Death

• Thistle – Scottish Descent

• Tree – Life

• Tree Sprouting – Life Everlasting

• Severed Branch – Mortality

• Tree Stump – Life Interrupted

• Tree Trunk – Brevity of Life

• Tree Trunk Leaning – Short Interrupted Life

• Urn – Immortality (Ancient Egyptian belief that life would be restored in the future through the vital organs placed in the urn.)

• Weeping Willow Tree – Mourning; Grief; Nature’s Lament

• Winged Face – Effigy of the Deceased Soul; the Soul in Flight

• Winged Skull – Flight of the Soul from Mortal man

• Wreath – Victory

• Wreath on Skull – Victory of Death over Life

• Wheat Strands or Sheaves – The Divine Harvest

GENERAL DEFINITIONS FOR BURIAL PLACES

Cairn:

A mound of stones erected as a memorial or marker.

Catacomb:

An underground cemetery consisting of chambers or tunnels with recesses for graves. The most celebrated catacombs are those near Rome, Italy. Cairo and Paris also have catacombs.

Cenotaph:

A monument erected honoring a dead person whose remains lie elsewhere.

Crypt:

An underground vault or chamber, especially one beneath a church that is used as a burial place.

Grave:

1. An excavation for the interment of a corpse.

2. A place of burial.

Mausoleum:

A large stately tomb or a building housing such a tomb or several tombs.

Tomb:

1. A grave or other place of burial.

2. A vault or chamber for burial of the dead.

3. A monument commemorating the dead.

Sepulchre:

A burial vault.

Vault:

A burial chamber, especially when underground.

Monument Typology:

Any structure placed over a grave should be considered a monument, whether it be a large elaborate tomb or a small wooden marker. For simplicity sake, we are dividing monuments into three separate categories; tombs, crypts, &c.; grave-houses and grave-shelters; and the smaller markers such as headstones and footstones.

Tombs

Megalith Style Monuments:

A very large stone forming part of a prehistoric structure. Sometimes used to describe a grave monument. Four large stones (one at each corner of a grave) then might be called a megalithic monument or structure.

Rectangular (Box) Shaped Burial Monuments

Box Tomb (Slab), Box Grave, Chest Tomb

Stone Tomb (Riprap with Slab Top)

Slot and Tab Tomb (Slab)

Table Tomb (With Ledger Stone Slab Top), Pedestal Tomb

Triangular Monuments (cairns)

Coffin Shaped Tomb

Shaped Stacked Stone Tomb

Shaped Stacked Stone Tomb

Stacked Stone Tomb

Step-Stone Tomb (Large Stone)

Step-Stone Tomb with Headstone and Footstone

Step-Stone Tomb (Large Stone) with Coffin Shaped Top

Step-Stone Tomb (Small Stone) with Headstone

Tent Grave (Slab Tent with Headstone and Footstone)

Tent Grave (Slab Tent without Headstone and Footstone)

Ledger Stone

Ledger Stone (Slab with Headstone and Footstone)

Ledger Stone (Slab without Headstone and Footstone)

Coffin Shaped Ledger Stone

Ledger Stone (Slab without Inscription)

Grave-houses and Grave-shelters (grave-box, grave-house, grave house, grave shed, grave shelter, lattice hut, spirit house)

Grave house (Wood on a Stone Foundation)

Grave Shelter (Wood)

USUAL GRAVE HOUSE MATERIALS

Brick

Concrete, also called “Cement”

Field Stone (fieldstone)

Limestone

Marble

Native Stone

Sandstone

Soapstone

Wood

GRAVE MARKERS, HEAD STONE TYPES

COMMON AND NOT SO COMMON GRAVE MARKER MATERIALS

Brick

Bronze

Cast Iron

Ceramic

Concrete, also improperly called “Cement”

Field Stone (fieldstone)

Granite

Limestone

Marble

Native Stone

Sandstone

Soapstone

White Bronze (zinc)

Wood

COMMON MARKER SHAPES

Round top

Column

Cross

Monolith

Monument

Obelisk

Pillar

Pyramid

Star of David

Foot Stone (footstone)

Head Stone (headstone)

Ledger Stone

Plinth (a base for a column, tomb, or grave marker)

Stone

Table Stone

Tomb Stone (tombstone)

Epitaph

ADORNMENTS FOR TOMBS AND MARKERS

Christian

Crosses

Independent Order of Odd Fellows (I.O.O.F.)

Jewish

Masonic, (Free and Accepted Masons – F.& A.M.)

Memento Mori (Dark Memento)

A reminder of death or mortality, especially a death-head or an angel of death.

Hatchment

A diamond-shaped panel or escutcheon bearing the coat of arms of a deceased person. Occasionally seen carved on headstones.