This is the second part of my two-part series on the history of Holland Landing, beginning with the organization of the community against the ruling Family Compact in Toronto. You can read part one here.

In 1837, the area around Newmarket and Holland Landing was to become rebel country.

Samuel Lount, the central figure in the rebel march to Toronto, was a farmer and blacksmith from Holland Landing. On the evening of Dec. 6, 1837, a wagon packed with old guns and pikes secretly forged in Holland Landing, shillelaghs, and provisions were sent down Yonge Street to Montgomery’s Tavern in the charge of John D. Willson of Sharon.

Little columns of men from East Gwillimbury, Whitchurch, and King struggled through the mud that were the concession roads. These farmers, mechanics, and professional men from the northern settlements were basically peaceful and law-abiding but had been driven to desperation when their grievances had been sneered at by the Family Compact.

We know that the operation was destined to fail, given the confusion of constantly changing orders, their lack of military training, arms and discipline. Blood was shed but the initial conflict was all over in a short time and the insurgents were soon in full flight, pursued by mounted troopers. Lount would soon be a martyr to their cause. You can read about it in fuller detail in my article about the Rebellion.

Charles Thompson of Holland Landing became a business success during the 1830s operating stagecoaches up and down Yonge Street and steamboats on Lake Simcoe. Thompson also became famous for his running of what is said to have been the colony’s first amusement park.

In 1842, Thompson moved to Toronto where he established the Summer Hill Park and Pleasure Grounds located where the David A. Balfour Park now sits on Summerhill Avenue, Mount Pleasant cutting right through the previous amusement park.

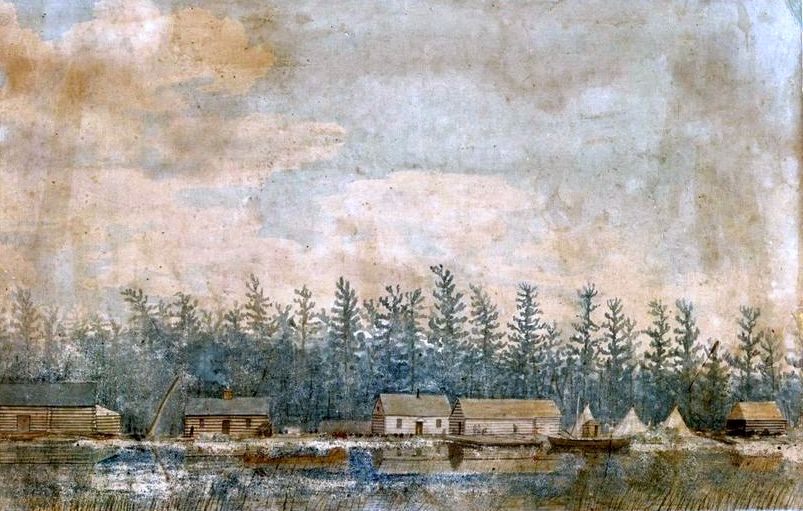

By 1846, the village boasted many stores and industries: including a brewery, a distillery, two tanneries, a foundry, three hotels and Ellerby’s carding and fulling mill with a woollen factory. The population was 260. Also, the village had a doctor, lawyer, a vet, a bank agent, craftsmen and a lady’s seminary.

The first mail carrier to transport the mail from the end of the stage route in Toronto to the first post office north of Newmarket, the military station of Penetanguishene, at a time when no road existed north of Holland Landing was a man named Eli Corbiere, a Holland Landing resident.

He had served as a clerk with the firm of Borland and Roe, the fur traders. He spoke French as fluently as he spoke English and was similarly familiar with the various Indigenous languages.

A.E. Coombs writes that Corbiere lived in Holland Landing just west of and quite close to the Grand Trunk Railway, close to the road that now leads to Bradford. As well as being the first mail carrier, he was also a local cobbler.

It is amazing that Corbiere carried the mail over more than 30 miles of undeveloped trail, through the woods and bogs and streams, to the point where the town of Barrie now stands, at that time just a few log cabins in the wilderness.

When Orillia and Penetang applied for mail service, Corbiere offered his services, becoming known as Fleetfoot Corbiere no doubt for his prowess. On one occasion, he made the run between Holland Landing and Penetang, 60 miles, between sunrise and sundown. Corbiere and his family rest in the pioneer Methodist burying ground on the hill north of the village of Sharon.

Another local Holland Landing man was Francis Gaudaur, the son of a French trader. He carried on an extensive trade with the Indigenous Peoples in the north as far north as Lake Superior. In time, he was to acquire great influence over the Indigenous communities, being employed by the government as an interpreter to the community around Rama.

During the days of 1837, the 18-year-old Gaudaur, travelling on foot and exposed to danger from the local insurgents, carried the government dispatches down Yonge from Holland Landing to Toronto and carried dispatches from Holland Landing up to the Penetang garrison.

He was also the lad who, on New Year’s Day 1838, escorted the 700 Indigenous from Holland Landing to Newmarket to join in the festivities.

Several oldtimers that I interviewed as a youth recalled being told of the road from Newmarket to Penetang when people were forced to come to Newmarket for their provisions. The round trip required three or four days.

The journey was made along the Penetang road to Barrie Bay, where it then continued by ice in the winter and boat in the summer to Holland Landing, and then again by road to Newmarket. It is said, too, that the first wagons to pass over this road were made locally by a man named White, a blacksmith, in 1826 or 1827.

As I mentioned earlier, creaking stagecoaches struggling over the hills of Yonge between York (Toronto) and Holland Landing, constituted the only public means of transport until 1853. These stages were ponderous affairs of the old English mail coach type drawn by four horses and had no springs to ease the jolting and the luggage was carried on top.

The first reference to public colonial transport I could find was from 1825 when a wagon service was inaugurated between York (Toronto) and Georgina, including Newmarket. These wagons continued to be used for passengers until 1830.

They were followed by the stage and passenger coach service established by George Playter and Sons in 1840s. These Yonge Street stages became a part of a complete system of transportation, including travel across Lake Simcoe.

An early owner, Charles Thompson, had an interest in two steamers, the Beaver and the Morning. The machinery for the latter was hauled up Yonge from Toronto on rollers made from sections of tree trunks, which required weeks to accomplish.

In 1832, a stage line was bought by William Weller, who was also the owner of stages from Kingston, Dundas and Niagara. These, too, ran in connection with the steamers on Lake Simcoe. After 1840, these wagons were replaced by improved vehicles designed for more comfort and more passengers.

It is said that a passenger had the choice to travel first, second or third class on the stage line. If he was in first class, he could keep his seat the entire way unless the coach turned over; if he was in second class the passenger was expected to dismount and walk whenever the road was bad; and if you were in third class, he was supposed to walk past the bad spots and procure a fence rail whenever a mud hole required the lifting of the coach.

A mail coach was dispatched from Toronto to Holland Landing three times weekly, Monday, Wednesday, and Friday; on Wednesday, that same stage carried mail for the remote places in the northern wilderness.

This once-a-week mail was then carried on horseback, sometimes on foot, sometimes by stage, according to the season and the state of the roads, although horseback was the mode usually employed. This state of affairs continued until the Rebellion of 1837, when public roads became more passable.

By 1848, the northern mail followed the following route. A passenger coach left Toronto every afternoon at 3 p.m. and was scheduled to arrive, via Newmarket, at Holland Landing at 8 p.m., about 34 miles north, but sometimes it was 2 a. m. when it arrived.

In turn, the carrier for Penetang was supposed to reach the post at 3 p.m. unless they were delayed by wolves. If there was a passenger for the north country on the stage, he then had to ride horseback behind the carrier.

William Benjamin Robinson filled the position of postmaster in Newmarket for 15 years, then gradually developed business interests, including a temporary post office further to the north in Holland Landing and County of Simcoe.

No record is available as to where that office was located but it seems safe to assume that it was in one of the stores that his stepfather, Elisha Beman, had established. Afterwards, an office was opened on Yonge Street, approximately one mile south of the Landing village. George Lount was appointed the first postmaster and Aaron Jakeway was his deputy.

Along Yonge Street, where the regular mail and passenger stage service was available, large patches of the forest remained despite the great strides made in the clearing. But the first shanties and early cabins had largely given way to substantial farmhouses, two-storied frame or roughcast, occasionally brick, often featuring a verandah around three sides.

Men who were already distinguished or destined to occupy a conspicuous part in the affairs of northern York County continued to arrive. It is interesting that in 1841, Capt. Bonnycastle wrote, when giving directions to Newmarket, that it would be worthwhile to take a ride down to Newmarket, a nice little village about four miles south from Holland Landing.

Smith’s Canadian Gazetteer of 1846 published an interesting description of Newmarket at that time with the following location: a village in the township of Whitchurch three miles from Holland Landing and about 30 miles from Toronto. Holland Landing was, it appears, a major point of reference.

Prior to the arrival of the railway, Holland Landing was the end of the stage route and was equal, if not superior, to Newmarket as a place of business. Bradford was regarded as having prospects. Aurora was known as the village of Machell’s Corner and the post office was called by that name. Sharon also was a busy little trade centre.

After the historic anchor had been placed in the park at Holland Landing in 1870, it seems Alexander Muir organized a huge public school picnic excursion to Holland Landing. It is reported that an immense crowd of men, women and children gathered about him as he told the story of the War of 1812-15 and of the days when the old village (Holland Landing) was a military station, back to the days of the Jesuits, who apparently had a stockade near the resting place of the anchor. Muir’s Maple Leaf Forever was featured for the occasion.

A story about the composition of this music appears in the Newmarket Era in January 1952 written by the daughter of Martin Taylor, one-time organist and choirmaster of Christ Church in Holland Landing. In it she recalls that her father wrote down the music for the song.

Muir had, for a time, resided in Holland Landing while teaching in Newmarket. Mrs. William S. McCullough talked of how Muir visited their home and worked with her father on the song, Muir humming the tune he had conceived, and her father wrote the music.

Apparently, Taylor was the first person to sing ‘The Maple Leaf Forever’ (before it was published) as a tenor solo at a benefit concert in the Landing at which Muir was so pleased with the reception that he then had the song published.

It is important to remember that several prominent merchant families in Newmarket did business in Holland Landing and are embedded in Holland Landing’s history. The name Denne was prominent in both Newmarket and Holland Landing for almost three quarters of a century.

Vincent Denne operated a butcher shop on Main Street in Newmarket, then went into the milling business, renting the Lukes mill on Huron Street and renting and operating the Red Mill in Holland Landing. In 1881, he enlarged and overhauled both mills, making the two mills the most modern rolling mills in Canada.

Part two of my series on the history of Holland Landing has come to an end. When I return to the topic, we will pick up the story with the saga of Mulock’s Canal and the part Holland Landing was to play.

Sources: East Gwillimbury in the Nineteenth Century – A centennial History of the Township of East Gwillimbury by Gladys M. Rolling; Articles from the Newmarket Era; The Yonge Street Story 1793 – 1860 by F. R. Berchem; The History of Simcoe County by Andrew F. Hunter; The History of Newmarket by Ethel Trewhella; Oral History Interviews Conducted by Richard MacLeod; Smith’s Canadian Gazetteer of 1846

*********************

Newmarket resident Richard MacLeod — the History Hound — has been a local historian for more than 40 years. He writes a weekly feature about our town’s history in partnership with Newmarket Today, conducts heritage lectures and walking tours of local interest, and leads local oral history interviews.